Finding Your Voice as a Legal Leader

General Counsel and Chief Legal Officers today face relentless pressure. It can feel easier to borrow the language of others—or even lose your voice altogether, retreating inward when the pressure mounts. Yet clarity, connection, and resilience in leadership begin with that voice. The “vowels of leadership” offer a practical framework to rediscover it: five mindsets that help legal leaders move beyond survival mode, find the confidence to lead, and the openness to draw strength from their teams.

What underlies all this is the simple fact that leadership is about others, not the leader. It involves developing other people under your charge, being of service, so that they in turn become leaders. This makes leadership truly sustainable and sets the foundations for a learning organization.

Let’s now consider the leadership vowels one-by-one and give voice to building a healthy, high-performing culture.

A is for Ambiguity

Experienced innovators are comfortable with ambiguity. They trust in the power of the process where a high level of ambiguity is a defining feature of the initial stages of a project, opening up new ways of tackling a problem, before focusing later on execution. Rather than something to be avoided it is viewed as a window of opportunity which combats a ‘copy and paste’ mentality from things that have been done before.

Business management offers many ambiguous paths that create cognitive dissonance in managers; operations v innovation, short-term v long-term, local v global. Senior leaders need to build an ambidextrous organization that has to look both ways at once in order to thrive. The F. Scott Fitzgerald quote seems to fit well here: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”

One of the consequences of ambiguity is a lack of certainty, of not knowing the answer. This can be uncomfortable for a senior leader. As Sarah O’Connor reflected in the FT in The lost art of admitting what you don’t know the more “expert” you become, the more you think you ought to know, and the more you fear your credibility will suffer if you ever admit otherwise. Yet not knowing opens the door to more collaboration and learning. Lazlo Bock, when he was People VP at Google talked of this ‘intellectual humility’:

“Google values the ability to take a step back and adopt the ideas of other people if they are better. It is about having 'intellectual humility.' Without humility it is impossible to learn.”

This was echoed in a recent McKinsey on Strategy podcast with US Navy Admiral Eric Olson, who said “no one’s too senior to be wrong. And no one’s too junior to have the best idea.”

In the Wall Street Journal’s The Best Bosses are Humble Bosses, studies are highlighted which show humility in leadership to inspire close teamwork, rapid learning, and high performance, saying that “humble people tend to be aware of their own weaknesses, eager to improve themselves, appreciative of others’ strengths and focused on goals beyond their own self-interest.”

What might this look like in practice? From giving credit to others, to asking others’ opinion, there are several actions that will make you a better leader and drive better team culture. Great legal leaders don’t eliminate ambiguity; they lean into the opportunity it provides and help others navigate it with confidence.

E is for Empathy

How may we fully understand the needs of another human being if we have not walked in their shoes? Empathy is a deeply human process that has a place at work. It allows us to engage with the whole person and sets the foundation for compassion and help, should that be required. It leads to sustainable high performance.

One of the key steps towards practicing empathy is listening. More talking and less listening can be an easy trap to fall into for senior leaders, yet a powerful example comes from Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, as detailed by former Microsoft VP Amit Fulay.

"A few weeks after I joined Microsoft, Satya randomly called me and my manager to chat. During those 30 minutes, he only asked questions. He asked about our thoughts on the product strategy, Microsoft’s culture, and what we thought needed change. Here you have this CEO of a $2 trillion company just listening to two new employees instead of telling us what to do. That’s remarkable. Later on, I realized that this is how Satya gathers signal. He’s really good at getting different points of view from different sources and then connecting the dots on what needs to be fixed. It’s remarkable that he can do this without falling into the temptation of telling you what to do."

As Satya himself wrote in his book, Hit Refresh: "Listening is the most important thing that I accomplished each day because it would build the foundation of my leadership for years to come."

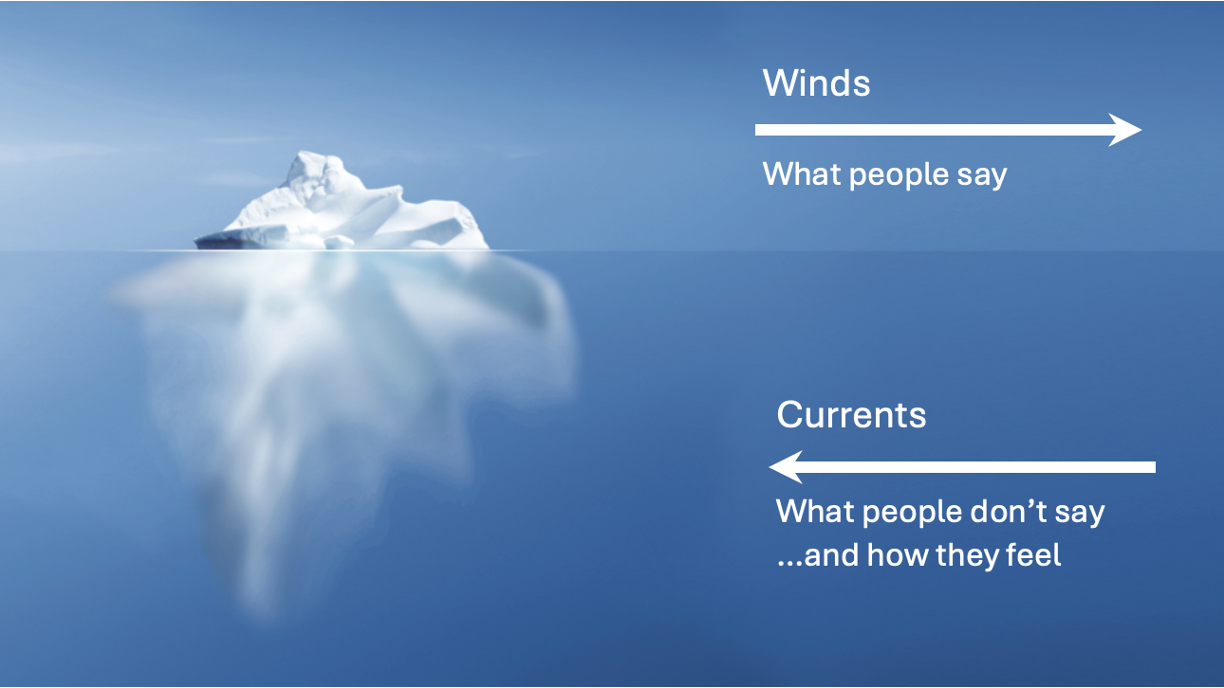

Listening doesn’t exist in isolation. Being able to formulate powerful questions is needed too. And both may be practiced by adopting a coaching mindset in your leadership. Listening without judgement, not offering the solution, a question-driven approach, are all hallmarks of the coaching process. Considering the iceberg model may help understand the overall mindset we aim to bring through coaching.

Teams and organisations, even people, can be viewed as an iceberg. What percentage of an iceberg is below the surface? On average, since ice has 9/10 of the density of water, 90% is submerged.

How do we move people and organisations? We often focus on the visible metrics, policies and strategies. The things people say. These are the winds for our iceberg.

Yet, the greater force is the hidden currents, acting on the far greater mass that is below the water line. These are the habits, values, prejudice, and fears—the emotional rather than the rational. It is what people don’t say.

Leadership todays involves ambiguity and complexity that reduces awareness and visibility. The winds will continue to serve an important purpose in taking us where we want to go, but how might you tune in to those hidden currents? That’s where practicing empathy produces significant value.

For GCs, empathy means more than listening. It’s about sensing pressure points early and shaping an environment where people can perform sustainably.

I is for Iteration

Iteration concerns the repeating element of a process. An iterative loop helps to accelerate progress in comparison to one long linear process, where there is less insight into the impact of your decisions, or, more specifically, the cause and effect.

Shane Parrish, writing in the Farnam Street newsletter captured the positive impact of iteration in our decision-making:

“The people who get the most done don’t agonize over decisions. It’s not because they have better judgement. They’ve just structured their lives so being wrong isn’t expensive. When mistakes are cheap, you can move fast and fix what doesn’t work. When mistakes are expensive, you overthink everything and still choose wrong. This is why startups can run circles around big companies. It’s not because they’re smarter, but because being wrong isn’t expensive.”

Former Telefónica CEO Jose María Álvarez-Pallete tried to adopt such an approach in the context of a large former state-owned telco, highlighting that his agile, fast decisions would prevent delay and the “multiplying effect on the organization.”

Iterating and experimenting is counter to our desire to ‘get it right first time’. It’s easy to feel an emotional connection to the first fully formed idea or concept we produce, yet for maximum value this should merely be regarded as the prototype, a primer for discussion that could, and should, be ripped apart.

Again, we return to humility and learning. In the New York Times article Why Trying New Things Is So Hard To Do Sendhi Mullainathan gives an economists view on experimentation, saying it is: “an act of humility, an acknowledgment that there is simply no way of knowing without trying something different.”

So, how can you simulate, experiment, or prototype more in your normal work rather than always trying to get it right first time? Lawyers already iterate of course—every draft contract, every re-worked clause is a step forward. The shift is to apply that same mindset to leadership itself: test, learn, refine.

Perhaps you consider the right conditions for experimentation, so that any possible failure is used as a learning opportunity rather than a catastrophe. Yet the example of World Health Organisation epidemiologist Dr. Michael Ryan during the initial stages of the COVID pandemic shows the value of such an approach in the most high-stakes environments.

In March 2020 as the COVID pandemic was raging worldwide and governments were slow to take the hard decisions, he made an impassioned plea at a press conference on the dangers of delay. With his recent experience of dealing with the ravages of the Ebola epidemic, he knew very well the hazards of hesitation, stating that: “everyone is afraid of the consequence of error, but the greatest error is not to move. Perfection is the enemy of the good.”

A final practical message for the Iteration vowel therefore; learn by doing, have a bias towards action, and embrace experimentation.

O is for Observation

Deep observation is another key skill of accomplished innovators. Former IDEO CEO Tim Brown said that once a day, we should stop and take a second look at some ordinary situation that you would normally look at only once (or not at all)—as if you were a detective at a crime scene. He said that by feeding our curiosity and immersing ourselves in the “super-normal” we develop incredibly rich insights into the unwritten rules that guide us through life.

Observation links closely to the ‘signaling’ that is referred to in the approach by Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella, and just like deep listening, is accompanied by asking powerful questions. And in your legal team signals could include the silence in a meeting, or the colleague who always turns their camera off.

When I was a young innovation consultant, I spent some time doing ethnographic field research in Mexico. As part of a new marketing campaign for a major multi-national, I conducted shadowing work across four major cities. I went into the homes of our marketing targets with my video camera and followed them during their normal day, including picking kids up from school and going to the supermarket.

The logic is that we learn much more about people and their needs when we see them in their natural environment. By observing and asking powerful questions, we can dig to a deeper level of insight that is not as available to us in an office-based work environment where bias and assumptions prevail.

It reminds me of a cartoon by Tom Fishburne in the book Talking to Humans. There are three men in an office, filled with computers, pizza, and post-it notes. One says:

“If I were our teenage girl target, I would love our new product. The other asks; “Have you actually talked to any to make sure?” The third chips in, “What? And leave this room?”

A one-minute observation may beat a 1,000-page report.

How can you get out of the office and into the field? What indeed is ‘the field’ for your sector and organisation?

More broadly, by focusing on the observation vowel you will get closer to identifying the long-held assumptions you need to challenge in order to move forward.

U is for Understanding

The previous elements of ambiguity, empathy, iteration and observation will lead to understanding, provided we pay attention to one more critical leadership characteristic: the ‘hold’. As busy professionals we often rush to action, believing in the necessity of motion for results. Yet the value of the pause cannot be overstated. Reflecting deeply on information gained through practicing ambiguity, empathy, iteration, and observation will yield significant insight and opportunity.

The field of adaptive leadership encourages managers to hold back from rapid definition of a management task in the workplace to open up new and fresh possibilities—akin perhaps to embracing the ambiguity we noted earlier.

Diagnosing and reframing the problem ought to be the focus, instead of jumping to the solution. Defining the right question is often more difficult than finding the right answer.

Reframing is one of the GC’s most powerful leadership tools. Take compliance: often viewed as a ‘cost,’ the GC can reposition it as an investment in trust capital—building reputation, winning investor confidence, and ultimately enabling growth.

In their book, The Art of Possibility, Benjamin and Rosamund Zander highlight the value of reframing as follows:

“Every problem, every dilemma, every dead end we find ourselves facing in life, only appears unsolvable inside a particular frame or point of view. Enlarge the box, or create another frame around the data, and problems vanish, while new opportunities appear.”

Holding space, especially in the midst of urgency and chaos, takes bravery, but it gives us the opportunity to reframe, and the very means of reducing that urgency and chaos.

At GCWN we see the same reframing at work in wellbeing: shifting it from risk reduction to value creation, from reactive care to proactive performance. Understanding, in this sense, is not just about interpreting the present but envisioning a more sustainable future.

Just as vowels give voice to our language, these five mindsets give voice to more human leadership in law. Ambiguity, Empathy, Iteration, Observation, and Understanding are not abstract ideals—they are daily practices. They shape how we listen, how we decide, how we connect.

And they remind us that wellbeing is not a separate agenda, but the foundation of clarity and performance.

The Leadership Vowels framework will form the basis of our next UK workshop at Pinsent Masons on the 7th October. You can request an invite to Building Cultures of Wellbeing via email here.