Heartfulness: From Autopilot to Awareness

Most senior legal leaders are exceptionally well trained in how to think. Years of education and experience have sharpened the mind to analyse risk, interpret complexity, and make decisions under pressure. Yet for many General Counsel, leadership is less a cognitive challenge than an energetic and emotional one: carrying responsibility for others, absorbing tension from the organisation, and holding steady when stakes are high. In this reality, the heart is not just a metaphor. It is the engine that sustains performance, the regulator of stress and recovery, and the quiet compass that shapes how we show up.

The Heart as Engine

The human heart is the engine room for everything you do. Every beat of that engine, which may beat up to 100,000 times per day, comes in the form of a wave. Pumping 7,500 litres of blood in a 24-hour period, tiny electrical currents drive the waves of movement that form the beating of your heart.

A small electrical shock is first produced by pacemaker cells at the top of your heart. This electrical activity travels down through the muscle, contracting and passing on the current from cell to cell. After each has fired, it becomes momentarily unable to do so again, as if exhausted and having a rest. Between one-tenth and one-fifth of a second later, the next shock starts the whole process again.

Much of our work over the past decade has focused on a simple but often overlooked truth: busy leaders have a heart. For something that beats up to 100,000 times a day how often do we listen to it? Many of us are indeed frightened to work it to its upper limit. Yet the heart is a muscle that needs to be maintained in good shape as like any other. It is a barometer of our present state of health.

The work of Chief Wellbeing Officer of the past decade is the foundation of GCWN, both initiatives with the heart at the centre.

The risk for modern leaders is not occasional intensity, but continuous presence in a middle zone—neither fully engaged nor genuinely recovering, the body remains in a prolonged stress response. Over time, this erodes resilience, narrows judgement, and compromises both performance and wellbeing.

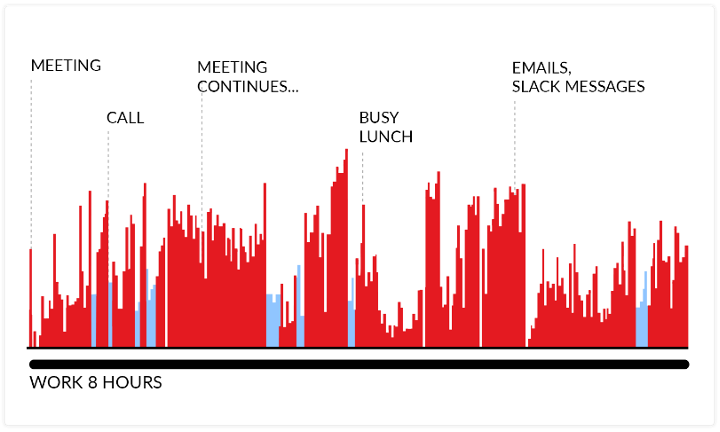

Heart rate variability (HRV) provides a window into the required balance, showing how the nervous system moves between activation and restoration, necessary for sustainable performance. A typical scenario is demonstrated in the HRV analysis of a busy executive in the graph below. Mild stress activation is shown (in red) as being more or less constant throughout the day, with the sympathetic nervous system (fight-or-flight) dominant.

Yet we are rhythmic beings. When escaping the always-on orthodoxy of busy work we are able to reap the rewards of the inevitable stress that exists in the modern working world. As Kelly McGonigle summarised in her 2013 TED Talk, stress really can be our friend. It serves us in so many ways, including memory, socialization, and cognitive performance. The following stress equation may be equally applied to the gym, as to the boardroom:

Growth = Stress + Recovery

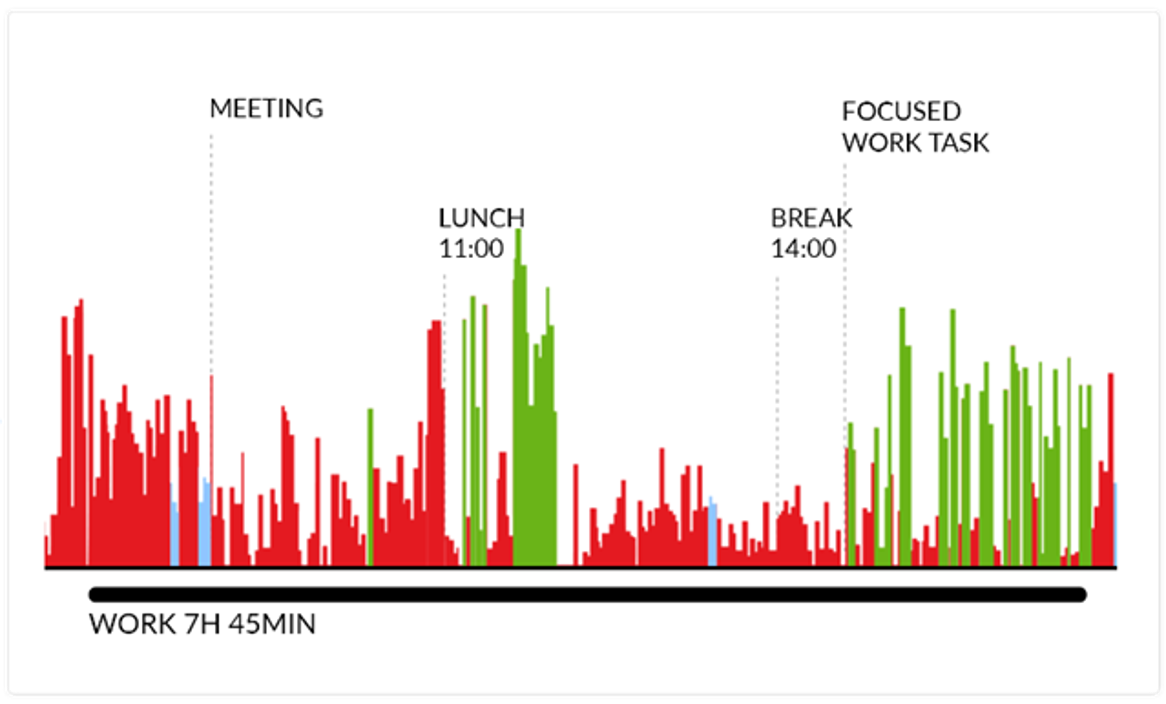

A redesigned day for the same busy executive is more natural, less artifical. More human, less machine-like. Stress is still evident (in red) yet the peaks are lower and the parasympathetic nervous system is activated too (in green).

With work representing so much of our life, we tend to focus on the brain at the expense of the heart. Yet the heart makes the brain better. Aerobic exercise improves memory, learning and self-control, as well as ‘cognitive reserve’ – essentially providing a buffer against cognitive disease including Alzheimer and Parkinson, later in life.

And the benefits can be reaped now, at any age. In Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain, Harvard Medical School Professor John Ratey reports on the rise in academic achievement of schoolchildren in Chicago, finding that exam performance in the morning was significantly boosted by running the mile immediately beforehand—an intense effort that took the schoolchildrens’ heart to its maximum level.

If you’ve neglected the heart as engine, it may feel overwhelming. So start simply.

Close your eyes.

Can you feel your heartbeat?

This is a simple test of assessing your interoception. A fast-moving area of study in neuroscience and psychology, it is the sense of what’s going on in your body, based on signals sent from your internal organs to the brain.

Scientists are understanding this sixth sense has enormous impact on our wellbeing. Build your interoception to create a bridge from the biological heart to the conscious heart. Understanding the heart biologically gives us data. Understanding it consciously gives us direction.

The Heart as Consciousness

Culturally, the heart represents the essence or centre of something and the means by which we give our all, truly able to inspire others. It is the seat of the things that make us human: compassion, joy, gratitude, and of course love.

The Ancient Egyptians believed the heart to be the core of all that made us uniquely human, doing all they could to preserve it during mummification, and believing the brain, in contrast, to be superfluous.

We feel with our heart—connecting to our emotional and spiritual selves. The heart as consciousness is therefore another critical view in our reflections.

Mindfulness is a well-known practice in the modern workplace which aims to improve awareness and presence, and Heartfulness is a similar meditation practice followed by millions around the world.

In its contemporary form, Heartfulness traces its roots to early twentieth-century India, emerging from a lineage of heart-centred meditation practices that were later systemised and brought to a global audience through the Heartfulness Institute. While grounded in ancient traditions, its current expression focuses on accessibility and practical application to daily life.

In The Heartfulness Way by Kamlesh D. Patel and Joshua Pollock, the heart is understood not only as a physical organ but as the centre of consciousness, a quiet inner space through which clarity, intuition, and purpose emerge. Though not tied to any particular religion it aims to connect our human existence to the Divine.

Whether that searching is for you or not, simply holding space has so many positives for our busy working lives. For many, it may feel similar to mindfulness meditation and reconnecting with what matters beneath the noise. In leadership terms, this perspective invites a shift from constant mental effort toward deeper awareness, enabling us to respond with greater presence and compassion.

It is a reminder that sustainable leadership does not arise solely from thinking harder, but from learning to listen inwardly. Holding space is as much about the heart as an engine as the heart as consciousness.

From here, the connection to leadership practice becomes clear. Inner regulation shapes outer behaviour. When leaders develop awareness at the level of the heart they become less reactive and more relational, which brings us to our final view of the heart.

The Heart as Connection

When awareness deepens at the level of the heart, leadership begins to change in subtle but significant ways. Presence replaces urgency. Listening becomes more generous. Decisions are made with greater steadiness rather than reactivity. This is where the biological and conscious dimensions of the heart meet the lived reality of leadership, shaping not only how we feel, but how others experience us. This relational force influences trust, psychological safety, and the culture that surrounds senior leaders.

Former New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern captured this shift as follows:

“You can be anxious, sensitive, kind and wear your heart on your sleeve. You can be a mother, or not, an ex-Mormon, or not, a nerd, a crier, a hugger – you can be all of these things, and not only can you be here – you can lead.”

Being fully human in a high-pressure legal profession is still rare, but increasingly essential. That humanity is supported by the biological condition of the heart. When stress becomes chronic and recovery is absent, decision-making narrows, patience shortens, and emotional availability declines. Conversely, when the heart is regulated, leaders gain access to greater clarity, empathy, and perspective. Polyvagal theory reinforces this, showing how our nervous system’s sense of safety directly shapes how we connect with others.

This connection translates into tangible leadership behaviours. The courage to admit uncertainty, the capacity to hold opposing views, the wisdom to pause before reacting, the empathy to truly hear others, and the self-awareness to recognise one’s own limits. Together, they describe a relational style of leadership grounded in emotional maturity and inner steadiness, qualities that matter deeply in high-pressure legal environments.

In a profession that prizes intellect, it is easy to overlook the heart until it begins to falter. Yet the heart is already doing the heavy lifting: sustaining energy, regulating emotion, and anchoring our capacity for judgement and connection. Heartfulness invites leaders to attend to the engine, consciousness, and relational force of the heart as a practical response to pressure and complexity.

This is embodied leadership and it can be practiced. Indeed, it needs to be practiced and experienced.

However we train our minds, we would do well not to neglect our hearts. Together, they will drive modern high-performance leadership.